Musical works presented in the form of a piece of software, such as Laurie Spiegel’s Music Mouse software[1] offer the listener direct interaction with the sounds and form of the piece. They enable new possibilities for electronic instruments to be “an actively participating extension of a musical person” (Spiegel 1986-8), and not just tools that execute the instructions of an operator.

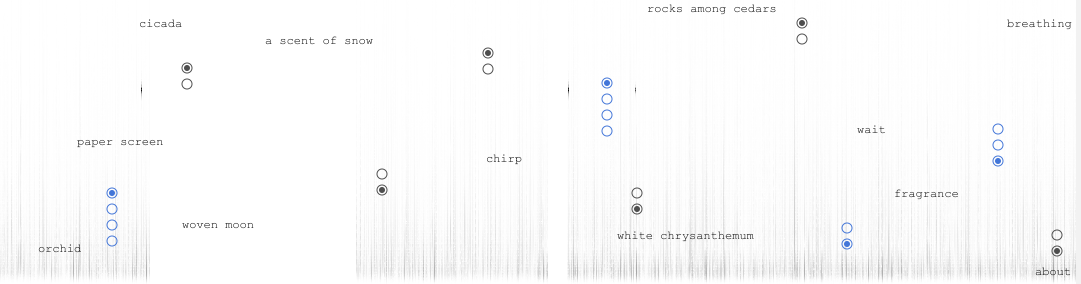

I am composing a work with the working title rainsweet remix to be presented as a piece of freely available software[2]. Intended as a study of interaction between technology and listener (or perhaps, performer), the work is composed of several types of sparsely occurring tones and clicks. The software has considerable agency over the trajectory of the piece, but the listener can decide which sonic components are sounding, as well as how long the piece lasts in time[3]. rainsweet remix can be seen as a continuation of rainsweet stillness (Maguire 2022), a rigidly composed work of mine in which very short sonic events are placed in a void of silence[4], and a cousin of Anne La Berge’s 2013-7 work TOO, in which tones, clicks, and pops can be controlled by a listener, in addition to a short poem read by La Berge. (La Berge 2017)

My compositional practice could be called non-dualist, dual aspect (Studenberg 2018), or any other such term that conveys the idea that the composer or performer, and their instrument, both have agency in the work. The thinking and doing in my work are one and the same: a piece is not performed from a score but devised in an active dialogue between the composer (or performer) and the instrument. They become a dyad[5] between myself and my tools (currently, synthesis). I embrace the electronic instruments that I use in my work as collaborators that can offer ideas as much as they can follow the instructions of the operator.

Consider Edgard Varèse’s motivations when he states, “I dream of instruments obedient to my thought” (Varèse 1917). Fell calls this sentiment “the nightmare of disobedient tools” (Fell 2021); that instruments that in any way demonstrate agency is something wrong: “Varèse’s distinction between the realm of imagination (thought) and the technical (instrument) follows the Cartesian division between mind and body, the mental and the physical.” (Fell 2021)

I develop practices with tools that have their own “physiognomies, histories, capacities, limitations” (Fell 2021) – such as modular synthesisers and audio programming environments – that aren’t directly obedient to the listener/performer but can enable a dyadic communication.

The listener can choose several variations of each sound in rainsweet remix, but these are limited and are not assigned conventional labels such as “preset 1/2” or “fast/slow”. One setting may be ‘denser’ than another, for instance, but otherwise the piece is making many of the decisions. This method of presenting the composition also means that once the listener leaves the dyad, the piece ends. Either the software is left open, and the sounds continue unanswered and to no one, or the listener closes the software, and the sounds cease. The dyad no longer exists (Scott and Marshall 2009).

As the various parameters in the piece are represented by abstract (and possibly irrelevant) text, the software that the piece is presented within could be viewed as a score or text piece for improvising with a group of semi-autonomous sounds, comparable to Ryoko Akama’s tada no series of text scores (Akama, こそこそ / koso koso 2013) in which ambiguous fragments of text encourage playful sound making and listening from the performer(s). It could be said that one intention of rainsweet remix’s texts is to abstract the technical nature of computer music to make the work more accessible, comparable to how Akama’s text pieces – originally written on walls, park benches, etc. and later presented as a series of cards – democratise experimental music by “looking for a way to communicate with people in term [sic] of mutual language.” (Akama, Sound in Life 2013)

All of this aims to highlight the complex mesh of interactions that can emerge from a simple set of sounds and controls. The piece encourages listening with close attention, that inform further decisions by the listener, that in turn re-configures the arrangement of the sounds, which inform more decisions from the listener, and so on.

In John Cage’s 1990-2 work Four6, performers of unspecified instruments can only choose when they play a specific, fixed sound within a time bracket (Cage, Four6 1992). rainsweet remix similarly restricts the actions of the listener, but perhaps in the inverse. In both works the sounds are placed in time by the performers and the composer. Four6’s sounds are placed in time by the performers, but only within the bounds set by Cage. rainsweet remix’s sounds are always occurring within a range set by myself but are made audible by the listener at any time they choose.

The short events in rainsweet remix form larger events in the listener’s mind. As Tony Conrad posits, "…it takes about a tenth of a second for anything at all to happen in the nervous system… a sequence of short durations, of very short events, will not be registered as such, but as a single duration that is indeterminately longer than the duration of each individual event…" (Conrad 2019)

The form of the piece is different in each listener’s mind[6], and each listening varies depending on how long they decide to interact with it. The sonic events are short in duration and spread in time[7] to instigate a deeper contemplation of duration for the listener, as they construct the piece’s structure from “the residual deposit of duration” (Barthes 1967) of the sounds. They are a constellation of possible interpretations. These short events are contrasted with longer tones that sound far in the background of the piece, further questioning perceptions of structure.

The text in the work is derived from haiku by Bashō. Each fragment of text deals with some form of natural phenomena: birds singing, the wind blowing, trees swaying. There is mention of a creaking gate, an extension of the wind. This could relate to how my pieces are not structured in a conventional form but are intended as an environment the listener can inhabit. I am fascinated by the texture of sounds, of them just being. I am reminded of a particular haiku by Bashō, “Spring air/woven moon/and plum scent” (Bashō 1985) and of Cage’s love of “sounds just as they are” (Cage, Listen (Écoute) 1991).

rainsweet remix is, in a sense, a work that encourages the listener to consider electronic sound as something beautiful in its own right, and something that can be viewed as natural, or the extension of a natural phenomenon (electricity). If we think of the text in TOO that reassures the listener that “is not Too [sic] late to listen in repose” (La Berge 2017), then rainsweet remix pursues a similar aim. Listen to the sounds and reflect on whatever you wish.

rainsweet remix - 12/01/23. Larger image.

Footnotes

[1] A partial web-based version of the software is available at https://teropa.info/musicmouse/ (Parviainen n.d.)(accessed 14/11/22)

[2] Built in the visual programming language Max. Anyone with a computer can run the software for free with a trial version of Max.

[3] Indeed, they are also free to choose the volume and location of listening, as with any fixed musical recording.

[4] A different form of software piece, rainsweet stillness was composed entirely in a Digital Audio Workstation (DAW), placing both new and previously recorded sounds from older projects on the timeline. Over the two years of composition, I regularly changed the order and number of sounds, but eventually decided to accept the piece as it was. It could be reworked indefinitely, but the form that was released on CD is considered as close to a ‘finished’ version as I was likely to get.

[5] In its sociological definition, “the smallest possible social group”. (Scott and Marshall 2009)

[6] There are infinite variables – the listener’s familiarity with such music for example, before we even consider their personal history, taste, or even physiological concerns such as their level of hearing.

[7] Some sounds, for instance, are triggered by highly filtered noise: sparse clicks that are not heard but used as triggers for events.

Bibliography

Akama, Ryoko. 2013. "こそこそ / koso koso." BORE 03. Oxford: Bore Publishing.

—. 2013. Flickr. September 2. Accessed December 13, 2022. https://www.flickr.com/photos/103584795@N06/9982643305/.

—. 2013. Sound in Life. September 28. Accessed December 13, 2022. https://akamaryoko.wordpress.com/2013/09/28/tada-no-score-project-flickr/.

Barthes, Roland. 1967. Writing Degree Zero. London: Jonathan Cape.

Bashō, Matsuo. 1985. On Love and Barley: Haiku of Basho. London: Penguin.

Cage, John. 1992. "Four6." Four6. Edition Peters.

1991. Listen (Écoute). Directed by M Sebestik, A D Grange, J Bidou and M Fano. Performed by John Cage.

Conrad, Tony. 2019. "On Duration." In Writings, by Tony Conrad, 524-33. Brooklyn: Primary Information.

Cummings, E. E. 1994. Complete Poems 1904-1962. New York: Liveright.

Descartes, R. 1968. Discourse on the Method and the Meditations. London: Penguin Classic.

Fell, Mark. 2021. Structure and Synthesis: The Anatomy of Practice. Falmouth: Urbanomic.

Ingold, Tim. 2001. "Beyond Art and Technology: The Anthropology of Skill." In Anthropological Perspectives on Technology, by M. B. Schiffer (Ed.), 17-31. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

johncage.org. n.d. Four6. Accessed December 12, 2022. https://johncage.org/pp/John-Cage-Work-Detail.cfm?work_ID=89.

Kavanagh, Patrick. 2005. Collected Poems. London: Penguin Classics.

La Berge, Anne. 2017. TOO. Accessed December 13, 2022. https://annelaberge.com/compositions/selected-available-works/too/.

Maguire, Phil. 2022. rainsweet stillness.

Parviainen, Tero. n.d. Music Mouse. Accessed November 11, 2022. https://teropa.info/musicmouse/.

Scott, John, and Gordon Marshall. 2009. A Dictionary of Sociology. 3rd. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Spiegel, Laurie. 1986-8. "The Music Mouse Manual." Music Mouse. Accessed December 13, 2022. http://musicmouse.com/mm_manual/mouse_manual.html.

Studenberg, Leopold. 2018. "Neutral Monism." The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Edited by Edward N. Zalta. September 21. Accessed December 10, 2022. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2018/entries/neutral-monism/.

Varèse, Edgard. 1917. "Que La Musique Sonne." 391 5.